Background: remixing packages in R

Open source software is made for remixing. When I first switched from STATA to R, I was comfortable using predefined packages and commands, but it quickly became apparent that R’s appeal lies in the power to write custom functions and packages. What’s more, because R is open source, these packages don’t have to be built from scratch. They’re best when they sample from others.

When I saw Rasmus Baath’s amazing beepr package retweeted, I knew I wanted to sample it. Beepr includes one function, beep(), which plays a sound when a script is done running. It’s immediately useful to me, as I am constantly running short 2-5 minute jobs, but getting distracted and spending 30 minutes away from my code because I don’t realize it’s done. Beepr’s built in sounds are pretty fun – beep("mario") and beep("treasure") play old-school video game celebrations, and you can include html links to wav files to play any .wav that exists on the internet.

For my beepr remix, I wanted to use ad libs from rap songs. I often want to shout “GUCCI” or “WE THE BEST” when a long script is done, but I have over the years come to understand that “most people” don’t “appreciate” this kind of action in a “workplace environment.” I can settle for letting DJ Khaled and Gucci Mane shout them for me.

If these had been on the internet in .wav form, I probably wouldn’t have spent any time learning how to scrape audio files from the internet and build them into a custom package. But they weren’t. Thus, BRRR was born.

It can be installed and run with the following command:

devtools::install_github("brooke-watson/BRRR")

library(BRRR)

# play a simple rap adlib in R

skrrrahh()For background on what BRRR does and how it got it’s name, the README is quite comprehensive. Modifying beepr to include different sounds was actually quite straightforward - getting the data was the interesting part. Here, I’ll walk through how I scraped a JavaScript website, extracted and downloaded over 300 mp3 files, and hosted them in a package on Github.

Javascript webscraping in R

# import packages

library(rvest)

library(stringr)

library(tidyverse)

library(purrr)

library(here)

library(beepr)

library(DT)Getting the audio files entailed a fair bit of preliminary work. I had to:

- Scrape TheRapBoard to find paths to all of the audio files.

- Download mp3 files from the website.

- Convert them from .mp3 to .wav format.

- Pare down from ~300 to ~50 sounds to keep the package (relatively) light.

- Put them in a folder that R would recognize and bundle into my package.

A note: web scraping can be a tremendously useful way to extract data from the internet, but it can cause real problems for some websites and should be done respectfully and ethically. This post from James Densmore lays out some guidelines for doing this responsibly. Before I did anything, I checked to see whether The Rap Board had a robots.txt file that prevented or provided specific instructions on how to scrape the site. I recommend doing this before any web scraping project - and keeping that in mind if you’re thinking of reproducing this script.

Download PhantomJS using homebrew

Httr and rvest are the two R packages that work together to scrape html websites. Usually, this works by using a browser extension called SelectorGadget to find all items styled with a particular CSS - actors in an IMDB table, for example. For more, check out the SelectorGadget vignette:

if(!require(rvest)) {

install.packages("rvest")

library(rvest)

}

vignette("selectorgadget")Unfortunately, this didn’t work for the website I wanted to scrape, which was written primarily in JavaScript. Instead, I adapted Florian Teschner’s instructions on using PhantomJS to convert the website into HTML. I wrapped this in a system() call inside R Studio, but it could just as easily be done from the command line.

Before we can do anything, we need to download and unzip PhantomJS. This can be done from the link, but if you have a Mac and insist on staying inside RStudio, below is some circuitous R code you can use to do just that. It first downloads Homebrew, if you don’t have it yet, and then downloads PhantomJS. Homebrew is an easy way to install packages onto a Mac from the terminal. PhantomJS calls itself “a headless WebKit scriptable with a JavaScript API”, which for our purposes means that it will convert a JavaScript website like Rap Board into html. This means we can get the paths to the .mp3 soundboard files really easily.

# donwload homebrew if it doesn't already exist

if(!dir.exists("/usr/local/Homebrew")) {

system('ruby -e "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install)"')

}

# download phantomjs using homebrew

if(!dir.exists("/usr/local/Cellar/phantomjs")) {

system("brew install phantomjs")

}Writing scrape.js

Next, we’ll write the JavaScript code to a js file called scrape.js. If you want to scrape a different JavaScript URL, we can change the path in the next function.

# write the javascript code to a new file, scrape.js

writeLines("var url = 'http://therapboard.com';

var page = new WebPage();

var fs = require('fs');

page.open(url, function (status) {

just_wait();

});

function just_wait() {

setTimeout(function() {

fs.write('1.html', page.content, 'w');

phantom.exit();

}, 2500);

}

", con = "scrape.js")Scraping TheRapBoard.com

This function takes scrape.js and the url of our choice (in this case, the url that hosts the audio files we need) and calls PhantomJS from the command line on a Mac. If you didn’t download PhantomJS using homebrew, you’ll need to include the path to your downloaded PhantomJS package as a phantompath argument. If you use Windows, this also is going to look different.

js_scrape <- function(url = "http://therapboard.com",

js_path = "scrape.js",

phantompath = "/usr/local/Cellar/phantomjs/2.1.1/bin/phantomjs"){

# this section will replace the url in scrape.js to whatever you want

lines <- readLines(js_path)

lines[1] <- paste0("var url ='", url ,"';")

writeLines(lines, js_path)

command = paste(phantompath, js_path, sep = " ")

system(command)

}

js_scrape()Extracting audio files

After converting the rap board’s website from Javascript into html, I could use rvest and dplyr package functions to get the mp3 paths into a format that I wanted. The code below required some fiddling with stringr and regex to convert a jumble of html into a list of file paths. It could be more succinct, but it works.

# read the newly created html file

html <- read_html("1.html")

setup <- html %>%

html_nodes("source") %>%

str_c("") %>%

as_tibble() %>%

filter(!str_detect(value, 'ogg"')) %>%

lapply(., str_replace, '<source src=\"', "http://therapboard.com/") %>%

lapply(., str_split, "\" type")

mp3s = map(seq_along(setup$value), ~setup$value[[.x]][1]) Downloading mp3s

Finally, I had the list of mp3 paths. I wrote a function to download the urls into an mp3s/ folder that I created inside the function. I used Sys.sleep() to introduce a random lag in between each download, which I hear is best practice.

download_mp3s = function(url) {

if(!dir.exists("mp3s")) {dir.create("mp3s")}

# create a place to put them if you haven't yet

url = url

destpath = stringr::str_replace(url, "http://therapboard.com/audio/", "mp3s/")

download.file(url, destfile = destpath)

Sys.sleep(sample(seq(1, 3, by=0.001), 1))

} Then, I waited. Fittingly, I used beepr to alert me when my script was done.

lapply(mp3s, download_mp3s)

beep("mario")Organizing an R package

Converting mp3s to wavs

Now that the mp3 files were downloaded into my computer, I had to convert them to .wav files so that they worked with the audio R package. I used ffmpeg to do this. It’s easiest to do this by downloading ffmepg from the website and running a command from the terminal, but we can wrap them in a system() call like such if we again insist on doing everything from within R. The text inside the system call loops over all the .mp3 files in the /mp3 folder and converts them to .wav, keeping the rest of the file name the same. I then moved them to their own folder and deleted the mp3s - we won’t need those anymore.

Again, command line syntax is different in Windows. Them’s the breaks. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

# convert mp3s to wav files

system('for file in mp3s/*.mp3; do

ffmpeg -i "$file" -acodec pcm_s16le -ac 1 -ar 44100 "${file%.mp3}".wav

done')

# make a new folder for the wav files

dir.create('wav')

# move wavs to the wav folder

system("mv mp3s/*.wav wav")

# delete the mp3s

unlink("mp3s", recursive = TRUE, force = TRUE)Cleaning up and filtering .wav file names

The audio files from The Rap Board don’t have much of a consistent structure for unique IDs. Some are numbered, while some include segments of the lyric. The numbered files don’t always fall in order. This is more than fine for them, but since we’ll often be calling particular sounds from inside the function by name, I don’t particularly want to have to remember whether Gucci yelling “BRRR” is called “gucci_brr” or “gucci_brrr” or, inexplicably, “gucci_14”, as it was when we downloaded it.

I was doing a lot of str_splitting, so I wrote a convenience function to extract the first component from the rest of the list.

extract_first = function(string, pattern) {

x = stringr::str_split(string, pattern)

y = purrr::map_chr(seq_along(string), ~x[[.x]][1])

}

# create a lookup table matching the artist to the unique .wav file

wavs = list.files("wav")

wav_names = map_chr(wavs, str_replace , ".wav", "")

artist = extract_first(wav_names, "_")

lookup_table = data_frame(wav_names, artist)We’re in a good shape - we now have a dataframe with the names of 319 wav files. That is way too many to include in a package. At this point, I went through all of them and chose my favorites, based on my personal preferences. This part is manual, arbitrary, and important.

selected = lookup_table %>%

filter(wav_names %in% c("2chainz_tru", "2chainz_whistle", "bigboi_1", "biggie_2", "bigsean_boi2", "bigsean_doit", "bigsean_holdup2", "bigsean_ohgod", "bigsean_stop", "bigsean_whoathere", "birdman_1", "birdman_4", "birdman_respeck", "busta_6", "chance_aghh2", "desiigner_rahhh", "diddy_5", "drake_5", "drake_worst", "drummaboy_1", "fetty_yeahbaby", "flava_1", "future_brrr", "gucci_1", "gucci_14", "gucci_4", "jayz_itsyoboy", "jayz5", "kendrick_tootoo", "khaled_blessup2", "khaled_majorkey3", "khaled_theydontwant", "khaled_wethebest", "liljon_2", "liljon_3", "nicki_laugh2", "pitbull_6", "ross_1", "ross_2", "schoolboy_yawk", "snoop_4", "soulja_5", "takeoff_money", "tpain1", "traviscott_straightup", "treysongz_uhunh", "trick_2", "waka_1", "weezy_4", "yg_skrrt"))Tidying file names

Luckily, the files tend to fall under a general artist_uniqueid naming convention. The next section cleans up the unique IDs. If a rapper has any sound board sounds, you’ll be able to call it with skrrrahh("name"). To cycle through the various sounds, use skrrrahh("name1"), skrrrahh("name2"), etc. until you get an error.

# make the filenames more consistent

filtered_names = selected %>%

group_by(artist) %>%

mutate(n = row_number()-1) %>%

mutate(newnames = paste0(artist, n))

# remove the "0s" so that you can call some files just by the artist name

filtered_names$newnames = map(filtered_names$newnames, str_replace,

pattern = "0", replacement = "") %>%

unlist()

# two are stilled a mess - let's fix these manually.

filtered_names$newnames = str_replace(filtered_names$newnames, "jayz5", "jayz1")

filtered_names$newnames = str_replace(filtered_names$newnames, "tpain1", "tpain")Finally, I couldn’t make this package without including Big Shaq. He’s not on the Rap Board yet, so I made his clip in garageband and manually dragged it into inst/adlibs. That means this walkthrough is not entirely reproducible, but as Ralph Waldo Emerson says, _“a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds”, so Please Do Not @ Me.

bigshaqdf = data.frame(wav_names = "bigshaq", artist = "bigshaq", n = 0, newnames = "bigshaq")

filtered_names = bind_rows(filtered_names, bigshaqdf) %>%

arrange(newnames)Let’s take a look at the table we used to transfer the old names to the new ones:

knitr::kable(head(filtered_names))| wav_names | artist | n | newnames |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2chainz_tru | 2chainz | 0 | 2chainz |

| 2chainz_whistle | 2chainz | 1 | 2chainz1 |

| bigboi_1 | bigboi | 0 | bigboi |

| biggie_2 | biggie | 0 | biggie |

| bigsean_boi2 | bigsean | 0 | bigsean |

| bigsean_doit | bigsean | 1 | bigsean1 |

Renaming file paths from within R

Now I have to use the information in the data frame to rename the actual files. The easiest way for me to do that is to rename them while moving them into a new directory. I can then delete the entire old directory.

Conveniently, R packages store all files that they need in the inst/ folder, so I have to get these babies there at some point. Let’s do it now.

# create a new directory, inst/adlibs

dir.create("inst")

dir.create("inst/adlibs")

# make character vectors that map the old file paths to the new file paths

filtered_names <- filtered_names %>%

mutate(old_filepaths = paste0("wav/", wav_names, ".wav"),

new_filepaths = paste0("inst/adlibs/", newnames, ".wav"))

# rename the old paths to the new paths

map2(filtered_names$old_filepaths, filtered_names$new_filepaths, file.rename)

# delete the old file path

unlink("wav", recursive = TRUE, force = TRUE)Remixing the beep() function

Now that I had all the audio files in the right place with the right names, I just had to change the name of my main function and update some paths.

Like beepr, I wanted BRRR to also have a single function. Mine is called skrrrahh(), named for 2017’s most iconic Roadman, Big Shaq.

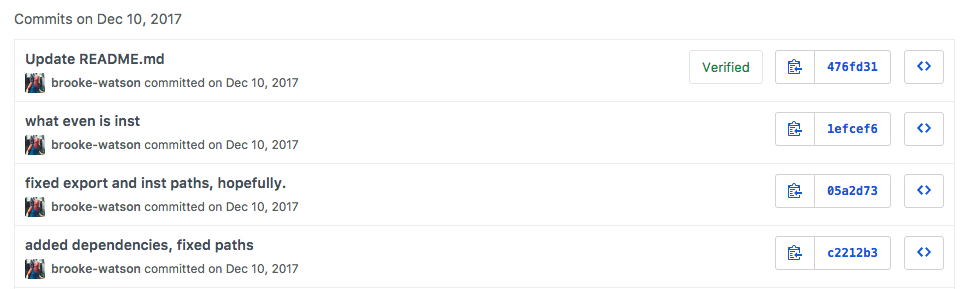

The bones of the function are the same. I started by cloning the beepr Github repo and fiddling around in the guts of the main function, beep(). Most of my changes were to internal file paths - including hard-coding links to to the new filenames we just generated. I mostly hacked at this using Sublime Text and heavy amounts of Copy-Paste. Really inquiring minds can see the changes in the commit log.

Wrapping it all into a package

I believe Hilary Parker’s post on making an R package from scratch is the seminal reference text for this activity. I’ve seen it attributed all over the internet, and as promised, it’s a tremendously simple and straightforward step-by-step guide.

I did run into a few hiccups along the way, due to my complete inexperience with roxygen. For future reference, or for anyone in a similar boat, here are some notes based on bugs and fixes I discovered:

- All documentation code begins with

#', not the single#. - You have to include

#'@exportin the documentation of every function if you want it to be available to use in the package. - I had issues when I included a space between the last documentation line and the first line of the function, and also when

@exportwasn’t the last line of my documentation. I’m not sure if this is truly necessary, but I’m superstitious enough to keep doing it this way.

For example, the bit between my documentation and my function looks like this:

#' ...(more documentation above)

#'@export

skrrrahh <- function(sound=26, expr = NULL) {Not like this:

#' @export

#' @params sound expr

#'

skrrrahh <- function(sound=26, expr = NULL) {If any of the functions rely on other packages, you have to

@importthem for the function to work properly. If the packages you’re importing are huge, and you only want to import certain functions, you can do that as well.Generally, especially if this is your first package, it’s best to shoot for a minimum viable product. MVPs may not include all the examples or links to other documentation that you will eventually want your code to have, but they get it up and running as quickly as possible. You can add additional documentation later. It’s also easier to troubleshoot issues if you’re building a package step-by-step. When you’ve got a ton of well-documented functions, it will be harder to identify the source of the problem if your package fails to build properly.

Maintaining an open source package in R

Again, Hilary and Jenny have created more and better instructions on installing a package locally and from Github, so I won’t repeat what’s already been done.

But once I pushed this to Github, I immediately became an open source developer and maintainer. That’s all it takes. Folks saw it on Twitter, got a good chuckle, and immediately started using it, fixing bugs and typos, and offering suggestions for the next version.

This is the thing I didn’t realize before building this package. When you make something open source, and put it out into the world, people will often just start fixing things for you, for free. I got lucky with BRRR - apparently, the Venn diagram overlap between rap nerds and stats nerds is much larger than I thought, and more people saw this package than I ever imagined. But this is the beauty of open source - projects become bigger, better, and more creative than they ever could if they live and die on one person’s computer. Four people have fixed bugs or typos in my repo, which I in turn built off the back of Rasmus’s. Someone has already ported beepr into Python. The community shared beepr with friends and colleagues they thought would like it.

Hopefully, someone else who has never made a package will take this and run with it, remixing the remix until it is unrecognizable. In the wise words of the Godfather of my very first R package: